Finding Your Roots

Chosen

Season 9 Episode 7 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

David Duchovny and Richard Kind trace their Jewish roots from Eastern Europe to the US.

Henry Louis Gates helps actors David Duchovny and Richard Kind trace their roots from Jewish communities in Eastern Europe to the United States—telling stories of triumph and tragedy that laid the groundwork for his guest’s success.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Chosen

Season 9 Episode 7 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates helps actors David Duchovny and Richard Kind trace their roots from Jewish communities in Eastern Europe to the United States—telling stories of triumph and tragedy that laid the groundwork for his guest’s success.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to Finding Your Roots.

In this episode, we'll meet actors David Duchovny and Richard Kind; two men who are about to hear the long-forgotten stories of their Jewish ancestors.

DUCHOVNY: I always just thought it was luck, you know.

In my mind, it was like, oh, they were lucky to have gotten out before the Holocaust, that was it.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: But now, I think it's more, they were smart.

GATES: Richard, according to his death certificate, Hyman was murdered.

KIND: He was murdered.

GATES: No talk of this in your family?

KIND: None!

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists combed through the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

And we've compiled everything into a book of life.

A record of all of our discoveries.

KIND: Well, ain't there a skeleton in my closet, huh?

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

DUCHOVNY: Oh, man.

We heard myths, we heard stories that it might be like this, but we never knew.

KIND: I'm learning, in name, where I came from.

GATES: David and Richard grew up knowing that their roots trace back to Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.

But that's about all that they knew, because when their families immigrated, a great deal of history was lost, destroyed, or willfully obscured.

In this episode, we'll recover that history, introducing my guests to ancestors with whom they share much more than a religious faith.

(theme music playing).

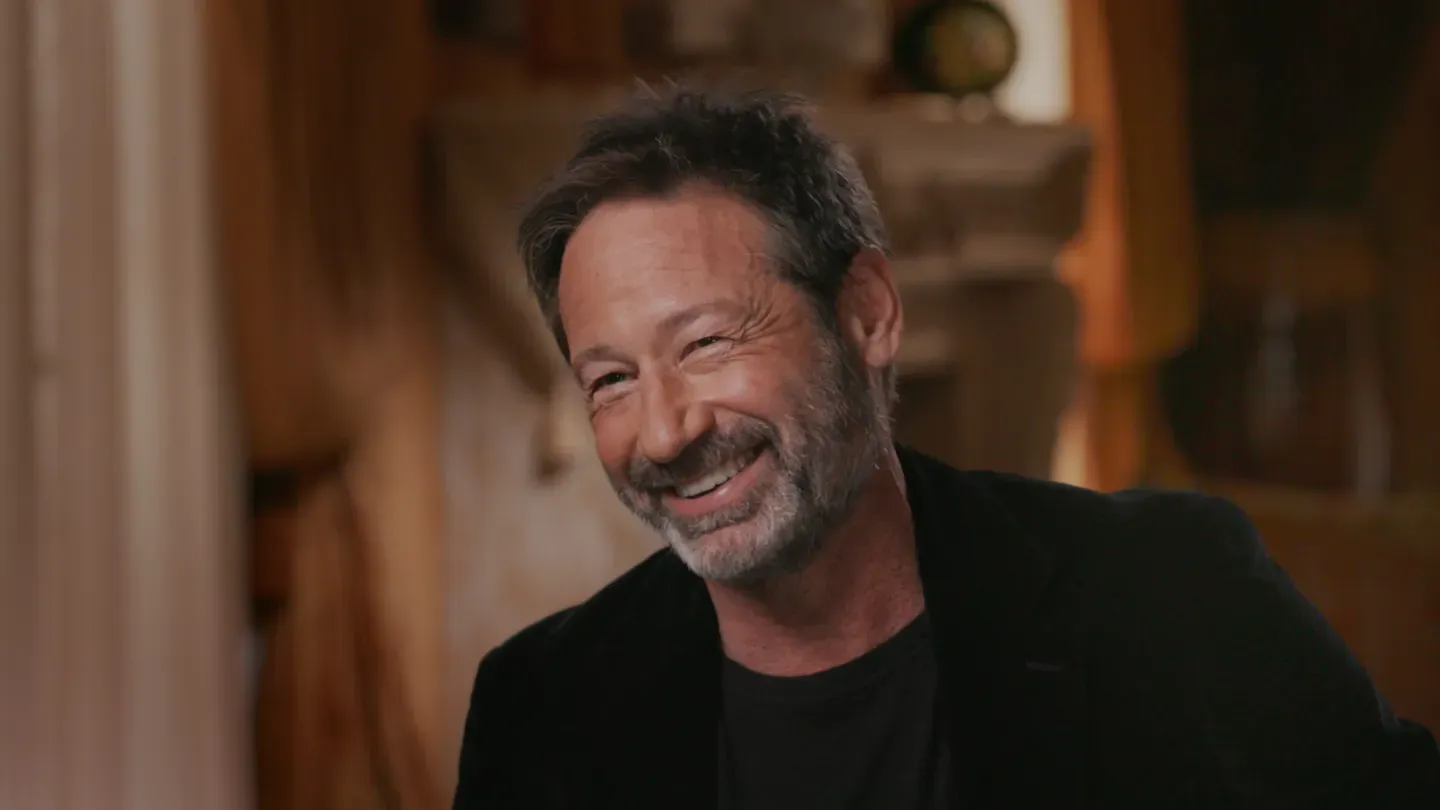

♪ (book closes) ♪ GATES: David Duchovny has an act.

Since 1993, when he came to fame on The X-Files, he's played an array of brooding, cerebral characters.

But beneath his cool exterior lies a restless spirit; a man who's been re-inventing himself his entire life.

David grew up in Manhattan, where his mother was a school teacher and his father an aspiring writer.

As a child, he dreamed of being a professional athlete, before setting out to follow in his parents footsteps.

At first he succeeded wildly.

After majoring in English at Princeton, David found himself in a PhD program at Yale, on track to be a professor.

But then he changed course once more, essentially on a whim.

DUCHOVNY: I had written poetry and I had written some prose and I was 22, 23 years old, and I was just thinking, "Well, this is a, this is a lonely existence."

GATES: Hmmm.

DUCHOVNY: And I, I wasn't a loner, I wasn't an...

I isolate to a certain degree, but I wasn't an isolated individual, and I wanted to, just like with sports, I wanted to play with other people.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

DUCHOVNY: I wanted to collaborate, and I wanted to pass the ball around, I didn't want to just to have the ball.

GATES: Right.

DUCHOVNY: So, plays, "Oh, maybe I should write plays."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

DUCHOVNY: And then, I thought, "Well, if I'm going to write plays, I should probably learn something about acting."

I mean, if I'm going to write words for an actor to say, "I should know what that's like," so I just...

There's so many productions, as you know, going on around Yale at all times.

GATES: Yeah, it's a great theater... DUCHOVNY: They need bodies.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: I was just a body.

It was like, "Oh yeah, this one line, go over here and do that," you know, so that's how I started.

GATES: What did your parents say when you told them that you were not going to get a PhD, you were going to act?

DUCHOVNY: Yeah.

Well, my father, my father was fine.

My father never really put that much, the hope or stock, into me being an academic.

My father was a pretty bohemian dude.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

DUCHOVNY: But my mother was mortified completely, uh, wanted me to finish my PhD, still wants me to finish my PhD, and it's no joke to me, I mean, every time I go over there, she's, she'll say, "What are you doing?

You could have a PhD!"

GATES: Right.

Fortunately, David's mother was unable to deter him.

A year after dropping out of Yale, he landed a bit part in Mike Nichols', Working Girl, and a flood of larger roles quickly followed.

Even so, David remained a questioning soul.

Indeed, when he first saw the script for The X-Files, he wasn't sure it was right for him.

DUCHOVNY: I was like, I was a young actor, I was like, "I'm not going to do TV, I'm going to be a movie actor," and uh... GATES: Mm-hmm.

"I'm an actor."

DUCHOVNY: Yes, exactly.

Yeah.

So that, that was my point of view, and I...

This, this, this script came along, and I thought it was really good, but I also thought it has no legs, I mean, it's about...

It's about aliens.

GATES: Right.

DUCHOVNY: And so, I'm not interested in that, nobody's interested in that, so I thought, "Okay, this is perfect, I'll...

If I get this job, I can shoot this very interesting pilot, and then it will, I'll get paid, and it will, and I'll go on to do my movies."

GATES: Wrong.

(laughter).

GATES: The X-Files, of course, would become a sensation, one of the most celebrated shows in television history.

And David's compelling character was a huge part of its success.

But David didn't let the role define him.

To the contrary; he continued to follow his own path, branching out from acting to writing novels and screenplays, directing a film.

And even releasing three albums as a singer/songwriter.

And now, after more than three decades in the limelight, David is at ease with his multifaceted career, even if he, and his mother, still wrestle with what it all means.

DUCHOVNY: I think I asked her, at one point, back when tabloids existed, you know, at the supermarket... GATES: Mm-hmm.

DUCHOVNY: And, uh, I said, you know, "What do you think when you see me on those, you know, you're checking out at the grocery and there's, you know, me, and whatever they're saying about me, that day," and uh, she said, "I just think it's weird, I just think that's my David, you know, I don't, I don't...

It doesn't, it's not the same thing."

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: And in a way, that's what it's like when you, when you first get that kind of, uh, fame, it's like there's two parts...

There's two separate identities.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

DUCHOVNY: There's the one that people own and think they know, and then there's the you who you've been since you came into consciousness, which doesn't really change.

GATES: My second guest is Richard Kind, famed for his roles on Curb Your Enthusiasm, Big Mouth, and A Serious Man.

With his unforgettable voice, and ability to inhabit almost any character, Richard seems as if he were born to act.

But appearances are deceiving.

Richard was actually born for something far more conventional.

He grew up in suburban New Jersey, where his father and his grandfather had run jewelry stores for decades.

So Richard's path was all laid out for him, until a teacher noticed that his true talents lay elsewhere.

KIND: I was being raised to have a jewelry store, two-and-a-half kids, join the country club... GATES: Right.

KIND: Da-dah-dah-dah-dah.

Now, what got me into acting...

When I was in fifth grade, the movie Oliver!

had come out.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: And we were looking through a list of what the, the kids' plays were for school.

And I asked, "Let's do Oliver!"

And he made me Fagin.

GATES: Oh, wow!

KIND: And I sang, ♪ In this life, one thing counts, ♪ ♪ in the bank, large amounts.

♪♪ And that's when I wanted to be an actor.

GATES: This realization would change Richard, and his family, forever.

By the time he was a teenager, he was obsessed with Broadway and had developed a highly unusual theater-going routine, with more than a little help from his parents.

KIND: I acclimated myself to taking the train from Trenton, New Jersey.

My mom would drop me off at the station at around 11:00.

I would get into Penn station.

I'd go to TKTS, buy a half-price ticket, go see a matinee.

Then in-between the matinee and the evening, I would go to Nathan's for two hot dogs and French fries.

I would go to the Drama bookstore.

And I would go to Sam Goody to look at records.

And then I'd go to a play at night.

GATES: Oh my God.

KIND: And then take the train home.

GATES: Alone?

KIND: Quite often, alone.

Very often alone.

GATES: You know, now we think of kids getting kidnapped, and we wouldn't ever let a... KIND: Oh, no, yeah.

GATES: Young child do that, you know?

KIND: Oh, no I, I, its...

I lived for it.

GATES: That's great.

KIND: Yeah.

GATES: You were lucky.

KIND: It was fantastic.

GATES: Richard's dedication paid off in a big way.

After college, and a stint with the legendary Second City comedy troupe, he was cast in the hit sitcom, Mad About You.

Leading to a prime role in another hit, Spin City.

Since then, Richard has been one of the great character actors of our time, moving effortlessly between stage and screen, comedy and drama.

But despite all he's accomplished, Richard has never lost his youthful enthusiasm for his craft; he simply loves what he does, and he's carefully managed his career to make the most of that passion.

KIND: When I was on Spin City, everybody said, "Oh, you'll be the breakout character."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: I didn't want to be a breakout character.

Then I'd be known for that character.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: When I was kid, Carroll O'Connor said, "Well, you know, I'm not just Archie Bunker."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: Sorry.

GATES: You are Archie Bunker.

KIND: You are.

GATES: Right.

KIND: I know you played a sheriff on a TV show.

GATES: Right.

KIND: I know you did other movies.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: You're Archie.

GATES: Right.

KIND: I never want to do that.

I want to go from this, to this, to this, to this.

And, if you walk down the street with me, a young kid will say, "Bing Bong."

A Jew will say Curb, or, um, um, Serious Man.

Um, somebody from the Midwest will say, um, Spin City.

Teenagers now say, Big Mouth.

It's crazy where they all, uh, where they all come from.

GATES: Right.

KIND: That's what I want to do.

I'm a smorgasbord.

GATES: Meeting my guests, it soon became clear that Richard and David share more than a profession; both have deep Jewish roots.

And both told me that while they felt connected to those roots culturally, they knew almost nothing about the lives of their Jewish ancestors.

It was time to change that.

I started with David.

David's father, Amram Duchovny, has eastern European Jews on every branch of his family tree, but he rarely spoke about them.

Indeed, he had a rather idiosyncratic approach to their very existence.

What was his relationship to his Jewish roots?

DUCHOVNY: Uh, ironic.

Every, every... All his relationships were ironic.

(laughter).

DUCHOVNY: He claims not to have been Bar Mitzvah'd.

He says his father, uh, took him out on an afternoon, tell your mother we're getting Bar Mitzvah'd, and they played pool all afternoon.

So, I was not raised in, in that way at all, we had a Christmas tree, my mother's Protestant, we, we kind of celebrated whatever, whatever... Whatever was most fun.

GATES: Right.

DUCHOVNY: We took off Jewish holidays, we took off Christian holidays, we barely worked.

GATES: Though David's father may have broken from the traditions of his religion, moving back one generation, we came to a man who was very much a product of those traditions.

Amram's father, David's grandfather, Moshe Duchovny.

Moshe died in New York in 1960, when David was an infant.

And his obituary details his deep involvement with New York's Jewish community.

DUCHOVNY: "Duchovny's death has thrown the Yiddish writing profession into deep sadness.

He was greatly respected and beloved by his colleagues, writers and numerous personal comrades and friends.

He always had a friendly smile for everyone and everyone liked to be around him.

Just Tuesday afternoon, he was on East Broadway with the writers and the editors.

Yesterday morning, he got up as usual and prepared to go to the office of Israel Bonds, where he was to serve as Yiddish press agent for the first day.

He felt a sudden pain in his legs and before his wife Julia could call the doctor, he passed.

Moshe Duchovny was a long-time teacher at the Workmen's Circle schools.

About 25 years ago, he became a regular contributor to The Morning Journal.

He was an outstanding reporter and also published a number of novels in the newspaper."

GATES: Have you ever read that?

DUCHOVNY: No.

Yeah.

Yeah, he was, you know, it's like you realize that these people who were just figures to you, they had full lives, you know, and, and, uh, just to think of him.

GATES: Hmm.

DUCHOVNY:I mean, I just thought that he was a reporter of some kind, I really didn't know and I knew that he wrote in Yiddish, but I didn't know how vibrant he was, and how busy.

GATES: Yeah, sounds like a pretty special guy.

DUCHOVNY: Yeah.

GATES: Moshe's early death not only robbed David of the chance to know his grandfather, it also ensured that his grandfather's story wasn't passed down.

David told me that knew that Moshe had been born in Eastern Europe, but beyond that, his life was a largely a mystery.

We set out to reconstruct it, starting with a petition for American citizenship, filed in 1940, by Moshe himself.

DUCHOVNY: "Morris Duchovny, occupation, journalist.

I was born in Berdychiv, Russia on June 10, 1901."

I don't know why that affects me.

He came a long way.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

(sighs).

DUCHOVNY: It just makes me so sad that I didn't get to meet him, really.

I know that my dad loved him.

My dad used to tell me, uh, he had this lingering guilt because, like the day or a few days before my dad... My grandfather died, he had called my father, and my father was busy, you know, at home, he had this baby, me, and he had my brother, who was four, and he said, "I can't talk, dad," and then he hung up.

GATES: Right.

DUCHOVNY: And that was the last time... GATES: Oh.

No, that's hard.

DUCHOVNY: That he talked to him, and I kind of feel that way, it's like, "Oh," you know, "I, I missed it," you know, we missed one another on this plane of existence, right?

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: But here he is coming back.

GATES: According to this petition, Moshe was born in a region of the Russian Empire that is now in northern Ukraine.

War and the Holocaust devastated this part of the world during the 20th century, and many records were lost or willfully destroyed.

Indeed, it's often impossible for us to learn anything at all about people who lived in this part of the world.

But with David, we got lucky.

In the 1897 Russian census, we found a listing for his family, and discovered that they supported themselves by running a dairy farm, a fact that took David by surprise.

DUCHOVNY: Wow.

GATES: You had never heard... DUCHOVNY: I've never... GATES: Even a hint of this?

DUCHOVNY: I, I've never milked a cow.

I, I would, I...

I wouldn't know which end to squeeze, to be honest with you, and my, my mind is just spinning with images of these people.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: Dairy farm.

GATES: David's family didn't remain on their farm for long.

When this census was recorded, they lived in what was known as, "The Pale of Settlement," a region where Russia confined and oppressed its Jewish population.

Within the Pale, Jewish people suffered an array of humiliating restrictions, and were vulnerable to outbreaks of anti-Semitic violence at any time.

Unsurprisingly, when they were permitted to leave, huge numbers did so.

Scholars estimate that between 1881 and 1915, more than one million Russian Jews emigrated out of the Pale, most to the United States.

But the Duchovny's chose a different destination; the Middle East.

DUCHOVNY: "List of people who traveled from Jaffa to Port Said on December 17, 1914, Avraham Duchovny, 40, origin Berdychiv, occupation innkeeper."

Innkeeper.

GATES: Innkeeper.

DUCHOVNY: "Doba, his wife, 40, Origin Berdychiv, their children; Leah, 17, origin , Moshe, 14, origin ."

GATES: Any idea what's going on there?

DUCHOVNY: No.

GATES: Your great-grandparents, Abraham and Doba, and their six children including your grandfather, Moshe, made their way from Russia to Jaffa, where they ran an inn.

(laughter).

DUCHOVNY: That is nuts.

GATES: And from there, they moved to Port Said, and do you know where Port Said is?

DUCHOVNY: No idea, where is it?

GATES: It's in Egypt.

DUCHOVNY: Wow.

So, they, they had these little kids, these little kids from Russia in Egypt, now?

Wow.

GATES: No family lore about any of this?

DUCHOVNY: No, nothing.

Nothing.

GATES: Although the details have been forgotten, the Duchovny's had embarked on a truly perilous journey.

Sometime around 1910, they traveled from Russia to the city of Jaffa, which is now in Israel but then was in Palestine, a part of the Ottoman Empire.

Unfortunately, their stay in the city was brief.

In 1914, the Ottomans entered World War I. by attacking Russia, foreign nationals who were living in the empire were required to become Ottoman citizens.

Those who refused faced a terrifying ordeal.

DUCHOVNY: "Turks slay and rob Jews at Jaffa.

Many acts of barbarism accompany their expulsion, children carried off, men thrown overboard, several who resented brutality to their wives murdered.

Cairo, Monday, December 21, information comes from Alexandria of great brutality on the part of the Turks toward the Jews of Jaffa, Palestine.

On Thursday, the Jewish quarter was invaded.

Bedouin police entered the houses and forced the inmates to accompany them immediately, allowing them small handbags only.

They were sent on board the Italian steamer Vincenzo Florio, bound for Alexandria.

The embarkation was relatively orderly till night fell, when there were lamentable scenes.

Police and boatmen joined in the fray, seized the Jews, took their bags and belongings and money, and tore off the jewels and trinkets of the women, they separated the children and their parents, and carried the former from the quayside.

There were desperate appeals on every side in the darkness, with heartrending screams."

Are you saying that my family was involved in that or is that just something that happened?

GATES: Your ancestors were among 6,000 Jewish residents of Jaffa, who were deported to Egypt in December of 1914.

DUCHOVNY: And treated like this?

GATES: Yeah.

(sighs).

GATES: Newspaper articles from the time indicate that many of Jaffa's Jews were robbed of all their possessions, meaning that David's ancestors would have arrived in Egypt with nothing.

Even so, they somehow managed to pick up the pieces of their lives and move forward, giving a surprising end to this story.

In the winter of 1916, less than two years after arriving in Egypt, Moshe and his father Abraham traveled to Greece, where they boarded a ship bound for the United States.

DUCHOVNY: "Abraam Douharmi, 39, married, occupation workman, nationality Russian, race Hebrew."

GATES: Hmm.

DUCHOVNY: Race is Hebrew.

"Last permanent residence Russia."

Douharmi.

GATES: David, you are looking at the very moment your great-grandfather, Abraham, and your grandfather, Moshe, arrived in America.

DUCHOVNY: I can't imagine their state of mind, I would, you know, you're always thinking of like the hope of the new world, right?

And they must have had some hope, but the fear and just the, the dislocation.

GATES: Mmm.

DUCHOVNY: Like, they've just, they've been moving quite a bit.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: For a couple years, and it's not going well, and they're just, they're going all over the world, they're looking for a home.

GATES: Yeah, and this wasn't even their preferred destination.

DUCHOVNY: No.

GATES: They just wanted to be in Palestine.

DUCHOVNY: Yeah.

GATES: And run their inn.

DUCHOVNY: Yeah.

Mmm.

Wow.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

DUCHOVNY: I'm proud.

They, they, they ran and they ran, and they, they got somewhere, you know, they... GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: They didn't give up.

They didn't give up.

What a world.

GATES: Turning from David to Richard Kind, we had another story of Jewish immigration to share.

Albeit one with a very different outcome.

Richard's maternal grandfather, Alvin Berson, was born in Manhattan in 1901.

His parents, just like the Duchovny's, were both from the Pale of Settlement, but Richard could see no trace of that experience in his grandfather.

To Richard, Alvin was a quintessential creation of his American hometown.

KIND: My grandfather, um, we would go on walks with him and my sister and I are huffing and puffing, keeping up with him and he would tell us, "This building is this, and this is where this happened and this..." A real New Yorker, truly.

Stern.

Very, very, sometimes horribly stern.

Uh, and, uh, loved a good joke, but was the furthest thing from a funny man.

Uh, the, the, the...

There's a smile on his face here.

I don't know where he got that.

Um, you, you can even see the tight lips.

He, he, that, that's how he was.

GATES: As it turns out, Alvin's smile belies a toughness that he likely inherited from his father, a man named Hyman Berson.

Hyman arrived in New York from Russia in 1896 and worked as a peddler on the Lower East Side.

This was one of the most common occupations for Jewish immigrants at the time, and it was grueling.

Peddlers generally pushed carts through the streets, selling low-priced goods, struggling just to feed their families.

But Hyman was one of the few who made it pay.

So much so that he left his cart behind, and ended up running a business of his own.

KIND: "Star Crayon Manufacturing Company, Hyman Berson, President.

Capital, $100,000."

That's a lot of money.

"224 Centre Street."

GATES: Did you know about this?

Your great-grandfather went from peddling to running his own company.

He manufactured crayons.

And you can see an example of the company's Crayarto Studio Crayons on the left.

What's it like to see that?

KIND: That's, this is silly.

That's what this feels like.

My relatives were in the crayon business.

GATES: They owned their own company.

KIND: That's nuts.

That's nuts.

GATES: In many ways, Richard's great-grandfather was a classic American success story.

In 1915, Hyman was one of three founders of Star Crayons.

His business would grow to include a factory in Brooklyn, and capital that would be worth over $1.7 million today.

But, unfortunately, Hyman's luck was about to run out.

KIND: "Certificate of death.

Full name Hyman Berson.

Age 55.

Date of death March 13th," there's a bad day, "1933.

The chief..." No!

(laughs) "The chief or determining cause of his death was gunshot wounds of neck."

Well, ain't there a skeleton in my closet, huh?

Wow.

I can hear him tingling.

Okay.

Wow.

GATES: Richard, according to his death certificate, Hyman was murdered.

KIND: He was murdered.

GATES: No talk of this in your family?

KIND: None!

But who talks about that?

GATES: Right.

KIND: Yeah.

No.

No.

No.

No.

No.

No.

My grandfather, no.

He would never talk about it now.

He would never talk about... That's, that's something he wouldn't address.

GATES: Right.

KIND: That's why he was... (mimics grandfather) Yeah.

GATES: Richard's grandfather was 31 years old when his father was killed, and Hyman wasn't the only victim of the crime.

His nephew Charles was also shot.

What's more, if newspaper reports are to be believed, the gunman was one of Hyman's business partners, a man named Simon Stern, and the crime was part of a larger scheme.

KIND: "Two partners shot, third questioned.

Simon Stern was taken for questioning in connection with the killing last night of his co-partner, Hyman Berson, and the wounding of the latter's nephew Charles Berson.

Berson's body was found in the stockroom of the company by a night watchman who also found the nephew lying unconscious in the office.

The nephew, a foreman for the company, was taken to the Cumberland Hospital suffering from a bullet wound in the neck and two in the spine."

So they meant it.

GATES: Yeah.

KIND: "Shortly after Stern had reached the police station, the dead man's three sons, Ralph, 23," who I knew, "Alvin, 32, and Benjamin, 26, arrived there.

Ralph Berson told the assistant district attorney and deputy chief inspector that his father and Stern had contemplated taking out life insurance policies for $10,000 each, naming each other as beneficiary and paying for the premiums out of the proceeds of the business."

GATES: Based on this article it would appear that Simon Stern killed your great-grandfather and wounded his nephew, Charles, to collect the insurance payment on a partnership policy.

KIND: Wow.

Okay.

GATES: This story was about to take a bizarre turn.

When Hyman's nephew Charles died from his wounds, Simon Stern was facing murder charges, and he mounted a curious defense.

Stern claimed that the Bersons had actually been killed by a racketeering organization, or a, "Trust," and that Hyman was involved in organized crime.

Leading Richard to wonder how much his grandfather actually knew about how his father ran the family business.

KIND: You know, my grandfather was a very moral man, so I think...

I never saw a side of him that was moral or immoral.

He just taught us lessons.

He didn't talk to us, he spoke to us.

GATES: Right.

KIND: He taught us lessons all the time.

"And this is what..." And maybe he really was affected by the death of his dad.

GATES: I'm sure he had to be.

KIND: Yeah.

GATES: Well, let's see what happened.

KIND: Okay.

GATES: We don't know if Stern's accusations were true.

There seems to have been a good deal of evidence to the contrary, including the fact that Charles Berson identified Stern as the gunman before he died.

But, in the end, the jury was not convinced.

Stern was acquitted.

And no one else was ever charged with the crime.

Meaning there's no way to know what really happened.

What do you make of that?

KIND: If I were a screenwriter, I'd say there was payment and things like that, underhanded work.

GATES: Right, who was betraying whom?

KIND: Right.

GATES: Right.

KIND: Right.

Right.

Right.

GATES: We don't know.

KIND: Yeah.

That's very interesting.

GATES: It is fascinating.

KIND: Yeah.

GATES: We haven't had many murdered ancestors sitting in the seat across the table from me.

KIND: Mm-hmm.

GATES: How about that?

KIND: And let me tell you something; I didn't think I'd be the one.

GATES: We now set out to trace the Berson family back in time, and we hit a wall.

There were no records to take us beyond Hyman's parents, Irving and Judah Berson.

Such walls are common in Jewish genealogy.

But when we shifted from Richard's mother's roots to his father's, we were able to make them fall away.

Our researchers traced Richard's direct paternal line back six generations, a feat we can rarely accomplish with any guest.

The key to it all was Richard's great-grandfather, Samuel Kind.

We found him on the passenger list for a ship that departed Hamburg, Germany for New York City in March of 1875.

KIND: "Name, Samuel Kind, age 17, occupation, gold worker.

Previous residence, Prague."

GATES: That record records the very moment your great-grandfather set out for America.

And look at the boat.

KIND: I see the boat.

GATES: That is the boat.

The S.S. Westphalia.

KIND: Wow.

GATES: Can you imagine making that journey alone... KIND: I can't.

GATES: At the age of 17?

Saying good-bye to your family, not knowing if you would ever see them again?

KIND: Without family.

GATES: No.

He went solo.

KIND: I can't, that I can't imagine.

GATES: No.

KIND: That's real courage.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

That's real courage.

KIND: Yeah.

That is.

GATES: This passenger list indicates that Samuel came from Prague, which was then the capital of what was known as the Kingdom of Bohemia.

The region has an ancient Jewish community, and a Bohemian census from the year 1793 shows that Samuel's grandfather, a man named Moises Katz, was a central part of that community.

KIND: "Moises Katz.

Occupation," well!

"Rabbi and Ritual Slaughterer."

GATES: You descend from a rabbi.

Did you have any idea?

KIND: No.

Never.

Never.

Never.

No.

GATES: Surprised?

KIND: Yeah.

Yeah, that's very surprising.

GATES: Yeah.

KIND: You know, I, as an actor and as a guy with an ego, I think my opinions are strong and always right.

GATES: Of course.

KIND: And I have strong political opinions.

Now I know where I get them.

GATES: Big time.

KIND: Yeah.

GATES: According to this record, Moises was from Germany, which was a telling detail, as it likely means that he was part of influx of German rabbis who came to Bohemia in the late 1700s.

What's more, Moises' gravestone indicates that his father, Falk Katz, was also a rabbi, suggesting that Richard comes from a long line of religious leaders.

KIND: Wow.

GATES: So they were recruiting rabbis into Bohemia.

KIND: And that's why he moved.

GATES: That's why we think.

It's logical... KIND: Just how many rabbis were there?

Was everybody a rabbi or, they were not?

GATES: No.

No, being a rabbi was very special.

KIND: Was special.

Yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

Big time.

You are the teacher.

Rabbi means teacher.

You kept the tradition.

KIND: Wow.

GATES: You were the most literate.

You welcome people into the world, and you usher them out.

KIND: And it passed it down, and it passed it on.

GATES: And you marked every ritual occasion in the life of your... KIND: Right.

And evidently it was a family business, because it got passed down.

GATES: Big time.

KIND: Yes.

GATES: How's it make you feel?

KIND: Smarter, or at least it's like getting, uh...

It's like The Wizard of Oz giving the Tin Man a diploma.

"Oh, look at, look at who's so smart."

Uh, so I, I, I think that's...

I, I can't believe it.

They're obvious leaders because the rabbi was the leader, obviously smart because they are scholars.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: And then, why didn't Samuel hold onto that?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: What told him to break away?

GATES: Right.

KIND: Not only from the rabbinic, uh, side of life, but from, uh, Bohemia.

GATES: Yes, absolutely.

KIND: Yeah.

What, what was it?

What was the catalyst?

GATES: 'Cause Broadway called, baby.

(laughter) We'd already told David Duchovny an incredible story, revealing how his grandfather Moshe and his great-grandfather Abraham came to America after a harrowing journey across Russia, Palestine, and Egypt.

But this story was not over.

When Moshe arrived in America, his mother Doba, and many of his siblings, were still back in Egypt.

It would take an enormous effort to reunite the family, culminating with a ship that arrived in the Port of New York on June 9th, 1920.

Would you please read who was on that ship?

DUCHOVNY: "Doba Duchovnia, age 36, Feiga Duchovnia, age 17, Herchel, age 15, Shmuel, age 13, Sima, age nine, race Jewish."

Not Hebrew now, now they're Jewish.

"Last permanent residence Alexandria, Egypt."

GATES: And that ship sailed from Marseille.

DUCHOVNY: That's from Marseille?

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: Wow.

GATES: Your family was reunited four years and three months after Abraham and Moshe first arrived in America.

Your great-grandmother Doba... DUCHOVNY: Wow.

GATES: And four of your grandfather's siblings joined them in New York City.

DUCHOVNY: Wow.

Sorry, I'm just saying wow.

I'm just thinking, like, so Moshe, my grandfather, from the ages of 14 to 18, does not see his mother... GATES: Mm-mm.

DUCHOVNY: Or, or siblings?

GATES: No.

DUCHOVNY: Then, all of a sudden, he's this 18-year-old kid, young man, and here comes mom... GATES: Right.

DUCHOVNY: And he's a New Yorker now kind of, and that's just, uh, it's a good story.

GATES: And in her mind, I mean, he's frozen in time, right?

DUCHOVNY: Yeah.

GATES: That had to be hard.

DUCHOVNY: Yeah.

Wow.

GATES: Tragically, Moshe and his mother were not able to enjoy their reunion for long; Doba died of tuberculosis just six weeks after arriving in America.

The family buried her in a cemetery in Queens, New York and emblazoned her gravestone with her photograph, allowing David the chance to glimpse her face for the very first time.

You are looking at Doba Duchovny, your great-grandmother.

DUCHOVNY: Hmm.

Where is that, Queens?

GATES: Queens, Montefiore Cemetery.

DUCHOVNY: I'll have to visit.

GATES: Do you see any family resemblance?

DUCHOVNY: Maybe.

I think she looks a little like my dad when he was like, he was kind of a chubby little kid.

Yeah, like my dad.

GATES: Yeah?

DUCHOVNY: Yeah, weirdly.

GATES: And we've translated the Hebrew inscription on Doba's grave.

Would you please read what it says?

(exhales sharply).

DUCHOVNY: "Here lies my wife and our beloved mother, modest and noteworthy in her ways, righteous and honest in her deeds and a righteous example to her children."

Mm, Doba.

Mm.

Yeah.

Well, she made it to the States, didn't she?

GATES: Yep, she made it and got the kids here.

DUCHOVNY: Yep.

GATES: Your great-grandfather, Abraham, was about 45 years old when he became a widower.

Can you imagine?

DUCHOVNY: No.

GATES: Mm.

DUCHOVNY: No.

But I'm just...

I'm also just so thankful that, um, you know, I know they didn't do it for me, but they, they gave my father a chance to have a different life and they gave his father, you know... GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: At his age of 14, you know.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: For whatever reasons, they, they were running or looking, they, they made some good decisions.

GATES: Yeah, they did.

DUCHOVNY: They made some good decisions.

I always just thought it was luck, you know.

In my mind, it was like, oh, they were lucky to have gotten out before the Holocaust, that was it.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: But now, I think it's more, they were smart.

You know, and they were, they were looking for opportunity, they were looking for safety.

GATES: There is one final beat to this story.

In the wake of his wife's death, David's great-grandfather Abraham returned to Palestine.

We found him in the 1928 census for Tel Aviv, a middle-aged man, living on his own, not far from the place where he'd once worked as an inn-keeper.

How about that?

Your family is full of surprises.

DUCHOVNY: They're, they're like...

They got a little crossover happening.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: They, they don't go exactly the way you think they're, they zig when you think they're going to zag.

GATES: Yes.

DUCHOVNY: So, he went back to Israel?

GATES: Yes.

Did you have any idea?

DUCHOVNY: No.

No.

GATES: He returned to where he had originally intended to immigrate.

DUCHOVNY: Wow.

GATES: And do you have any idea if Moshe ever went to visit?

DUCHOVNY: God, I don't know.

I'm just thinking Moshe was 18 when he went back, when Avraham went back?

So he was a young man?

I guess he could take care of himself and, they maybe never saw each other again, I don't know.

GATES: Yeah.

Would you please turn the page?

David, this is a gravestone is Israel's Nahalat Yitzhak Cemetery.

Would you please read the translation of the Hebrew inscription?

(sighs).

DUCHOVNY: "Here rests the honorable man, Abraham Dukhovny departed December 5, 1942 at age 68."

Mmm.

GATES: That is your great-grandfather's grave in Israel.

What's it like to see that?

DUCHOVNY: You know, my life has been so easy compared to them.

GATES: Hmm.

DUCHOVNY: You know, I, I didn't grow up with a bunch of money, but I grew up in Manhattan, and my parents were, you know, middle-class folks, they worked, I ate, I stayed at the same apartment, you know, I, I, I didn't fear for my life.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

DUCHOVNY: I didn't think we were going to be forced to move.

I, it was solid.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

DUCHOVNY: I had a solid childhood, you know.

Uhm, but just a few years earlier, that would not have been the case, had I been born... GATES: 3,000 miles away.

DUCHOVNY: Yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: So, I'm just lucky in that way, and the question becomes, you know, what, what do you owe or you know what's your responsibility?

GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: I don't know.

GATES: We'd already shown Richard Kind how ancestors on both sides of his family tree immigrated to the United States.

But not all of his family remained in this country.

Richard's third great grandfather, a man named Meyer Wacht, was born in what is now Poland.

He came to America in 1891 and, in the ensuing years, much of his family followed him, including a nephew named Avraham Wacht.

Avraham settled in New York, alongside three of his brothers.

But his new home, apparently, did not suit him.

Sometime before 1910, he decided to return to Poland, where he married and started a family in the small town of Narew.

The decision would have terrible consequences.

Did you ever wonder if you had any relatives in Europe during World War II?

KIND: Yes, and I sort of threw my arms up and said, "I haven't got anybody.

I, nobody."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: It's like I was very lucky.

I know a lot of people...

I know nobody who was in the 9/11, uh, buildings.

The Trade Towers.

And I never knew anybody who was related, who might have gone to the camps.

GATES: Could you please turn the page?

KIND: I'm gonna cry, aren't I?

Oh, wow.

GATES: That's Warsaw, the capital of Poland, and those are Nazi troops.

Richard, this is the brother that went back.

KIND: Yep.

GATES: Three stayed, and one went back.

KIND: And one went back.

Luck of the draw.

GATES: In June of 1941, the German Army entered Narew.

Avraham Wacht and his wife and children were among the town's roughly 300 Jewish residents.

They were soon forced into an area of less than five acres, effectively establishing a closed ghetto.

Incredibly, the only known account of this ghetto was written by Avraham's son, a man named Leibel Wacht.

Leibel was roughly 28 years old at the time, and his words are dreadful to read.

KIND: "On the 28th of July, 1941, the Gestapo came and demanded that the shtetl pay tribute, one kilo of gold, ten kilo of silver, and 100,000 rubles.

My father, Avraham Wacht, was told to collect the money.

The Germans took the money and then beat him badly.

On October 8th, 1941, the Germans surrounded the shtetl and all non-skilled men were taken.

Those who tried to run were shot.

They were beaten badly, and all their last possessions taken."

GATES: So what's it like to learn that you had relatives who experienced this?

KIND: Well, any time I hear about the Holocaust, of course I'm gonna have this reaction.

I, it's one of those things where I, where I hold the Holocaust as the great inhumanity, uh, the, it's, it's awful, and yet, to try and, and find the personal place, other than being a Jew, I never could.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: Again, I, I can.

GATES: In November of 1942, the Germans liquidated the Narew ghetto.

Most of its population ended up in the gas chambers of the Treblinka death camp.

Miraculously, Leibel managed to escape.

But his family was not so fortunate.

In the archives of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, we found over 20 testimonials written by Leibel documenting the fates of people whom he knew.

Among these symbolic tombstones, we saw that his father Avraham, his three siblings, and his five-year-old nephew had all perished at the hands of the Nazis.

KIND: So these were all my relatives.

GATES: These are your family.

So you never thought you had such a tangible connection to the Holocaust.

KIND: No, I didn't.

Mm-hmm.

GATES: And you've heard of... KIND: But, but again, forgive me, it, I, I, I have, it's not a tangible, but I always felt it.

GATES: Right.

KIND: I, I always have.

GATES: Sure.

It's your people.

KIND: So, it's my people.

GATES: Right.

KIND: And, and it's my people, it's, you know, it's everything, it's man, it's, you know, it's... GATES: Yeah.

KIND: Because of somebody's race or religion or whatever it is.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: It's just horrible.

GATES: There is a grace note to this story.

Following the war, Leibel married and had children of his own.

He was one of only a handful who survived the Narew ghetto.

And in the archives of Yad Vashem, he described how he did it, in a way that's truly heart-warming.

It seems that Leibel was saved due to his relationship with a Polish farmer named Andrzej Iwaniuk, who, together with his family, chanced everything to help his Jewish friend.

KIND: "In 1942, Iwaniuk helped me escape the liquidation of the ghetto and took me in.

He prepared a hiding spot for me in his barn, provided me with food and warm clothing in the winter, and once a week, prepared a hot bath for me.

In this hiding spot," oh my God, "I survived until May 28th, 1944, when the Germans evacuated.

By helping me, the Iwaniuks were aware that they risked their lives."

Aww.

"It's to them that I owe my life."

And then the family.

GATES: Yeah.

KIND: Wow.

GATES: He survived because a local farmer and his family hid Leibel in their barn for two years.

What do you make of that?

KIND: Every, everything's right about that story.

Everything is right.

GATES: Yeah.

KIND: It fills in all the blanks; the bravery of the family that hid him.

GATES: Yeah.

KIND: This guy, having to live there, under a barn.

Those nightmares, having to survive that.

A bath once a week, food.

GATES: Yeah.

KIND: That's fantastic.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for Richard and David.

It was time to show them their full family trees... DUCHOVNY: Wow, wow.

GATES: Filled with branches stretching back to Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.

And dotted by ancestors who left those communities behind.

You have DNA from all these people, man.

Seeing it all laid out allowed each man to reflect on how their own lives had been shaped by these journeys.

DUCHOVNY: I have a sense of place that I didn't have before.

Uhm, like I said, I don't identify as Jewish or as having a Jewish history, really.

Clearly, I do, on, on this side of my family.

GATES: Big time.

DUCHOVNY: I feel the presence of, of all these people... GATES: Yeah.

DUCHOVNY: You know, in the room, right now.

KIND: All of this speaks to; I did not get here alone.

GATES: Right.

You didn't.

KIND: I just didn't.

GATES: No.

KIND: And I'm well aware of that.

GATES: You're standing on shoulders.

KIND: Right.

Of course.

And I knew that, always accepted it, but to see the paper... GATES: Mm-hmm.

KIND: This, this astounds me.

GATES: My time with my guests was running out, but there was a surprise still to come.

When we compared their DNA, to that of other people who have been in the series, we found a match for David.

Evidence within his own chromosomes of a relative that he never knew he had.

DUCHOVNY: No way!

GATES: Yes!

John Leguizamo.

DUCHOVNY: I know him!

GATES: Oh, you do?

DUCHOVNY: Yeah!

He's a friend of mine!

That's awesome.

GATES: David shares an identical segment of his 15th chromosome with his friend and fellow actor John Leguizamo.

What's more, he also shares this DNA with John's mother, who has a small amount of Jewish ancestry.

Suggesting that all three have a common Jewish ancestor somewhere in the distant branches of their family trees.

Isn't that wild?

DUCHOVNY: That is crazy.

GATES: Go figure.

DUCHOVNY: That is really crazy.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with David Duchovny and Richard Kind.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests, on another episode of Finding Your Roots.

Video has Closed Captions

David Duchovny and Richard Kind trace their Jewish roots from Europe and the Middle East. (32s)

I'm Gonna Cry Aren't I?:Richard Kind's Holocaust Connection

Video has Closed Captions

Much to his surprise, actor Richard Kind discovers that he had ancestors in the Holocaust. (5m 34s)

Why Did David Duchovny's Family Come to America Then Leave?

Video has Closed Captions

David Duchovny traces his family journey to New York, separation and reunion. (7m 19s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: